COVID-19 Is Exposing and Widening Systemic Inequities In The Triangle

From where to build schools and supermarkets to how the government should distribute funds, the U.S. Census tells us who we are and where we’re going as a nation. The “who” is everything from the age of state residents to the race and ethnicity of everyone counted. And according to Census data published in 2017, North Carolina’s population is becoming more diverse with the percentage of White residents dropping and the Hispanic population growing among other changes.

But despite the shift toward diversity, White residents still represent nearly three-quarters of the state’s total population (with 7.4 million of them calling this state home), while Black residents represent 22% and Hispanics 9%.

Diversity in this instance does not mean equity. In an equitable society, the outcomes experienced by the different demographics of residents would be representative of the total sum. That’s not the case for COVID-19 cases and deaths in North Carolina, unless you’re White.

And with the kind of representation described above, it makes sense that White residents would also represent a majority of COVID-19 cases and deaths statewide.

North Carolina has reported more than 3,600 known deaths from the novel coronavirus since it emerged as part of the cultural and medical zeitgeist in March 2020. Of those cases, White residents account for 60% — falling below their total population representation. Comparatively, deaths of Black residents account for 30%, 8% higher than their total representation.

The widening gaps are no secret either. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that Hispanic and Black U.S. residents are three times more likely to contract the disease, and twice as likely to die from it, when compared to White residents.

Pepe Caudillo, Director of the Brentwood Boys and Girls Club, is seeing firsthand how COVID-19 is ravaging the Hispanic community. He has seen neighbors contract the virus, fall ill, and still have to go to work. And his experience isn’t unique.

Throughout the Triangle, Hispanic communities are contracting COVID-19 at a dramatically higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group. In fact, while less than 10% of North Carolina’s entire population identifies as Hispanic, the population accounts for 33% of the state’s total COVID-19 cases. 9% of those cases have resulted in death.

“They have to work. Low-income families have to work. They live on a day-to-day basis,” explains Caudillo when asked to explain the higher contraction rate. “They have to eat and pay the bills.”

The data ultimately speaks for itself: COVID-19 is exposing incredible racial disparities in the United States and the Triangle area is no exception. Here’s what else we’re seeing.

COVID-19 Cases by County

According to information published by the New York Times in July, Durham and Wake counties, Black residents at that time were contracting the virus at double the rate of White residents. In Orange County, Black residents’ infection rates were three times higher than that of White residents.

Hispanic residents in Johnston County were experiencing double the infection rate of White residents. The infection rate was four times higher for Hispanic residents in Wake County. And in Durham County? Six Hispanic residents contract COVID-19 for every one White resident.

So how does this happen?

Breaking Down the Disparity

First, let’s be clear. COVID-19 is not more contagious or deadly to any single racial or ethnic group. While Black individuals are more likely to be diagnosed with hyper-specific diseases like sickle cell anemia, the general biology between ethnic and racial groups is nearly identical across the board.

The factors that lead these groups to have more adverse outcomes with the virus have nothing to do with biology. They’re systemic.

And the effects of inequitable systems on marginalized communities aren’t just experienced in healthcare, these systems also affect someone’s ability to secure stable housing, gain rightful employment opportunities, access educational opportunities, and more.

Here’s what those disparities look like within certain sectors during (and outside of) the pandemic.

Disparate Health Outcomes Among Communities of Color

Just because we’re all battling the same pandemic doesn’t mean we’re receiving the same level of care now or have previously. The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) published a report in 2005 that found that Black and minority patients are less likely to receive kidney dialysis or transplants and often receive less than average treatments for strokes. In another study, NAM found that Black patients received “older, cheaper, and more conservative” treatments for heart disease than white patients.

Systemic issues also lead to higher hospitalization rates among Black Americans, which can affect the severity of individual COVID-19 cases. For instance, Black Americans are more likely to suffer from asthma and other lung diseases not because of the color of their skin, but because 71% of them live in communities that violate federal air standards. Black Americans also have 1/10th of the net wealth of White Americans, making it harder to purchase and maintain adequate health insurance, further exacerbating these health disparities.

COVID-19 Related Housing Disparities

Many families are facing major financial challenges during this pandemic as a result of losing work. These circumstances and the stress it brings can negatively impact anyone but Black and Hispanic communities are feeling the stress at a drastically higher rate.

Black, Hispanic, mixed-race, or other minority communities are double, and in some cases three times as likely to not know how they are going to pay for their housing next month. These numbers are likely to increase further with the end of housing moratoriums and eviction freezes.

And this is all happening in communities where rates of house burden — which is the label given to families who pay more than 30% of their monthly income toward housing — is as high as 50%.

These startling realities mean people are forced to make tough decisions surrounding healthcare and employment.

COVID-19 Related Financial Disparities

About 1 in 6 Black workers in America work in frontline jobs. They, along with Hispanic Americans, are more likely to continue working in-person throughout the pandemic than their White counterparts because they are more likely to be working jobs that have been deemed “essential.” Physically reporting to work puts them at increased risk for exposure and thus increases the likelihood they will spread it to their friends and family.

Here in the Triangle, Orange County Health Director Quintana Williams sees firsthand the predicament these communities have been put in.

“[The Black and Hispanic communities] are the essential workers. A lot of the work they do, like housekeeping and construction, are the infrastructure of our community. And so they’re the ones getting up every day, going out, and potentially being exposed to this virus.”

For so many individuals, the solution is certainly not as simple as quitting their jobs. Black and Hispanic communities have historically battled financial disparities in America. Just take a look at how North Carolinians spent their stimulus checks:

- Nearly one-in-five White residents were able to put most, if not all, of their stimulus check into some form of savings account.

- One-in-fifty Black North Carolinians were able to do the same.

- Over 225,000 Hispanic or Latinx North Carolinians did not receive or expect to receive a stimulus check at all.

For those reasons and more, it’s clear that quitting work to stay home and healthy is simply not an option for many people — and disproportionately they’re people of color.

COVID-19 Has Increased Food Insecurity for Certain Demographics

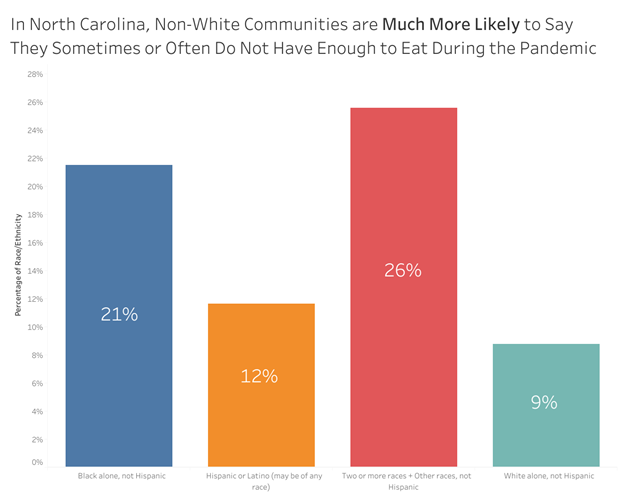

Food security is another side-effect of the pandemic that is disproportionately affecting minority communities.

During this pandemic, more than 200,000 Black and Hispanic North Carolinians report sometimes or often not having enough to eat, compared to 64,000 White residents. The effects of food insecurity can include developmental delays in children, loss of employment, and a plethora of serious health issues.

These disparities create a vicious cycle that continues to amplify the health, food, education, financial, and other fields where minority communities continue to struggle.

How Can We Help?

First, we can take practical steps to reduce the spread of the virus.

Pepe Caudillo believes one of the major reasons why the Hispanic community has been so heavily impacted by the virus has been due to a lack of Spanish-language information.

“The community should organize a more effective, functional way to communicate with those who don’t speak English. Immigrants have been here for years and we still have problems communicating with [them].”

Pepe also points out there are administrative barriers, like requiring Social Security numbers at some testing sites, that limit some members of the Latinx community from being tested. If individuals don’t have a social, he suggests assigning them a caseworker to relay the results and follow up. “We’re all in this together,” he said.

Quintana Williams thinks communities need to get stricter about following existing guidance.

“People want to get out. But we are safer at home. So we need to limit movement and activity as much as possible. Whenever we are out and about, please wear a face covering…because it works.”

Another way that people can help is by donating to the nonprofits going above and beyond to support residents during this time of crisis.

Over 1,100 Triangle residents have chosen to do so by donating to United Way of the Greater Triangle’s Rapid Response Fund, which was launched in March 2020 to provide funding to local nonprofits supporting residents with critical resources including food, hygiene supplies, childcare, and housing support. With more than $1.4M raised since, the organization has been able to provide these impacts locally:

- 508,740 healthy and nutritious meals have been provided to the most vulnerable populations in the greater triangle

- 4,108 people have been provided emergency rental assistance and emergency housing services

- 23,214 children have been provided the resources necessary to support their educational needs while out of school

- 37,512 adults and children received necessary medications, products, and services to address mental and physical health needs

For more information, visit the United Way of the Greater Triangle’s Rapid Response Fund resources page.

The more difficult step, one that will require a lot of work, is dismantling the systems of oppression that have forced our minority communities into this situation. Continuing to invest in and support minority-owned businesses, promoting equity in education and healthcare, and overhauling how the criminal justice system operates are just a few steps in the long journey that our region needs to embark on in order to become an anti-racist society.

United Way of the Greater Triangle is committed to doing its part to promote equity and anti-racism in Wake, Durham, Orange, and Johnston Counties, NC. Click here for more information about United Way’s equity journey to date. To support establishing the Triangle as an anti-racist community, please consider donating to United Way’s Anti-Racism Community Fund.